Alibaba: Why we do not own Shares

Introduction

Our ability to generate healthy long-term returns and protect downside is as much about avoiding stocks that risk permanent capital loss as it is about owning good long-term compounders. In the last quarterly, we illustrated our process using one of our top holdings (Marico). In this quarterly, we will explain why we don’t own shares in one of the popular Emerging Market companies, Alibaba Group Holding Ltd (Alibaba).

Alibaba

Alibaba is a Chinese Internet behemoth with a market capitalisation of more than $600 billion. The popular narrative is that Jack Ma, a highly capable Hangzhou-based English teacher and tour guide with an inspired vision, built a business from nothing with a group of sixteen friends from his apartment in 1999. They’ve gone on to build a business spanning e-commerce, food delivery, cloud computing, consumer finance, media and more. The company has grown at a breakneck pace in a market where opportunities appear limitless and delivered high returns on invested capital in the process.

Investors have rewarded this narrative with Alibaba’s stock delivering an impressive 25% annual return since its IPO in 2014. It has beaten not just the Emerging Markets and Chinese indices by wide margins but also edged out the Nasdaq during this period.

On the surface, the Alibaba story is indeed fascinating, but through detailed analysis over the years we have concluded differently.

Our analysis of Alibaba is consistent with how we research all companies in our investible universe. We start by understanding the business’ purpose, before evaluating the quality of its stewardship, franchise, and financials. Lastly, we study the long-term growth potential, to determine a fair valuation.

Purpose

Alibaba states that its mission is to make business easy anywhere in the world and their core e-commerce franchise does indeed appear aligned with this purpose; they have provided a complete solution for merchants to reach consumers across China (and increasingly across the world).

However, the company’s diversification into seemingly unrelated and often unprofitable areas lead us to doubt the true purpose of Alibaba. We will revisit the question of purpose later in this note and argue that Alibaba’s true purpose is by necessity misaligned with minority investors.

Quality of Stewardship

Governance

The starting point in our assessment of stewardship is to study a company’s incorporation history. We are looking to avoid companies with strong government ties and hints of crony capitalism, because these businesses are not as resilient as they may first appear. We also prefer to steer clear of businesses that are influenced by the government as these are not run with the best interests of shareholders in mind.

Emerging Markets often have fragile institutions and limited rule of law. If a business is built with the help of the government, what happens when the political powers change their minds? Or what happens if the key people in the government are replaced? If the government decides to start challenging a business, there is no recourse at all. Such government connections can go from being a powerful moat to a liability at the stroke of a pen.

A number of Alibaba’s pre-IPO investors in 2014 had strong connections to the Shanghai faction of the government under President Jiang Zemin. There was Boyu Capital, established by Alvin Jiang, the grandson of Jiang Zemin; New Horizon Capital, which was co-founded by Wen Jiabao’s son, Winston Wen; and CITIC Capital, headed by princelings Wang Jun and Chen Yuan1.

This CITIC connection was evident for the wrong reasons soon after IPO, when Alibaba bought a company called CITIC21CN where Wang Jun and Chen Yuan served as Chairman and Vice Chairwoman. The business, which had not made a profit in eight years, did not even have a functioning website and growth prospects were limited. Nevertheless, Alibaba’s investment resulted in a windfall profit for Ms Chen worth a reported $500 million1.

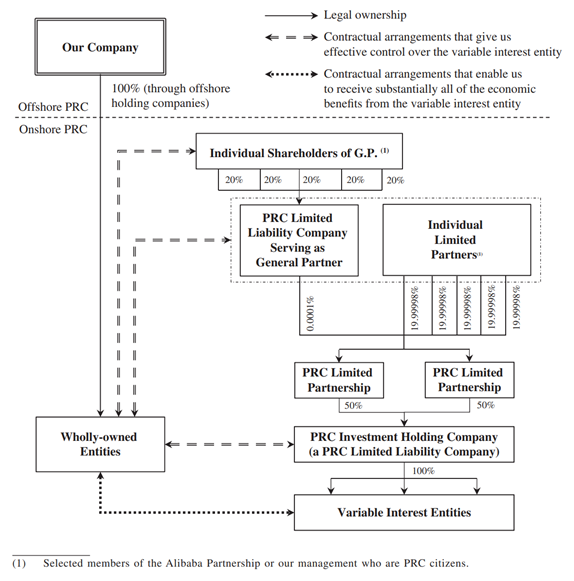

The incorporation history leads us to the ownership structure. We are looking for transparent and simple arrangements where we can find alignment investing alongside the key stewards of a business. In the case of Alibaba, the company is structured as follows:

Source: Alibaba filings

It has been well documented that VIE (Variable Interest Entity) structures are fragile in nature, operating in a legally grey area which is subject to the whims of regulators in China2. And yet the ubiquity of VIEs, which account for more than $1 trillion of stock market value, have made most investors sanguine to the tail risk of political interference. It is worth reiterating that through such VIE arrangements shareholders do not own the Chinese assets or the rights to the residual cashflows. Instead, they rely on contractual arrangements with the VIE. In this context, it is important to understand the ownership structure of any particular VIE to determine whether the individuals in charge are trustworthy and aligned with minority shareholders.

The Alibaba VIE structure was historically owned by Jack Ma and his long-time but elusive associate, Simon Xie, meaning investors were exposed to key man risk. Then in 2018, with much fanfare, Alibaba’s VIE ownership was distributed between two limited partnerships3 controlled by the Alibaba Partnership (known as Lakeside Partners), a group of 36 senior members of the organisation. The Alibaba Partnership also has the right to nominate the majority of the company’s board of directors; this dual-class shareholding is what disqualified Alibaba from a Hong Kong listing in 2014.

When Jack Ma stepped down as Chairman of Alibaba and passed the torch onto his protégé, Daniel Zhang, many investors cheered the corporate governance improvement. Not only was key man risk eliminated but the event allowed investors to draw a line in the sand and move on from Jack Ma’s past misdemeanours.

However, Jack Ma’s perpetual membership at the partnership and ownership of Ant Financial allows him to effectively control the partnership and seize licenses held in Alibaba’s VIEs4. It is through an even more complex web of contracts and relationships that Jack Ma continues to control Alibaba despite stepping down as Chairman and owning less than 5% of the company. It is no wonder that having figured out a mechanism by which he can retain control of the company, he has been reducing his ownership. This means Jack Ma remains the key steward, so an investment in Alibaba requires trusting Jack Ma.

History dictates that it is difficult to trust Jack Ma. In 2011, he controversially spun off Alipay (later renamed Ant Financial) and took control of the asset, in what remains the most notorious abuse of the VIE concept. With no means of recourse, Alibaba’s foreign partner Yahoo! was forced to accept significantly diluted commercial terms on their investment in Alipay. The Alipay controversy had such a negative impact on the Alibaba share price that management decided to delist the stock and take it private. To recall, Alibaba has now been listed three times.

Controversy around the shareholding structure of Ant Financial has persisted over the years. In 2019, Alibaba converted its profit share into a 33% stake in Ant Financial, making it the second largest shareholder after Junshun Equity Partnership, a vehicle controlled by Jack Ma, Simon Xie, and close associates. The continued presence of an increasingly outspoken Jack Ma influenced the recent suspension of the Ant Financial IPO. It was the latest reminder of how Alibaba, or at least Jack Ma, appears increasingly misaligned with the political status quo.

Alipay is not the only episode to raise questions around trust. Related party transactions and acquisitions have been a matter of habit for the Alibaba Partnership. In April 2014, Alibaba gave Simon Xie a $1 billion loan which he used to purchase a 20% stake in Wasu Media5 through an entity that was jointly owned by Jack Ma and Simon Xie. Alibaba claimed that they were not able to invest in Wasu Media directly because of Chinese regulations and that investing through Mr. Xie’s entity was the only way. In fact, Alibaba has regularly invested alongside Yunfeng Capital, a Shanghai based private equity company that was established by Jack Ma in 2010. The list of such related party transactions runs long and as recently as 2019 Alibaba Pictures gave a $103 million loan to struggling film studio Huayi Brothers Media in which Jack Ma has a considerable stake6. The lines between Alibaba’s shareholder interests and Jack Ma’s personal interests are very blurry, and at odds with our philosophy of backing clean and well aligned ownership structures.

Alibaba’s share-based compensation expenses are also alarmingly high. Over the past five years, Alibaba has paid its management nearly $17 billion in stock-based compensation, which equates to a third of stated net income. In contrast, for Tencent and Netease these figures were at 10% and 15% respectively.

Capital Stewardship

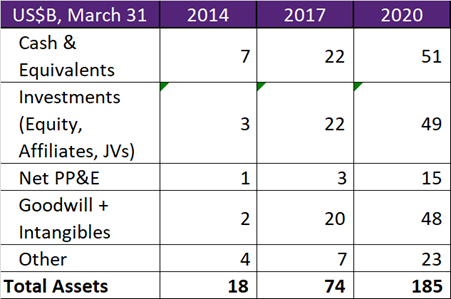

Since Alibaba’s IPO, the asset base has grown tenfold from $18 billion to $185 billion or 48% per year.

Source: Company Filings

However, this asset growth has mostly been driven by acquisitions and self-reported asset revaluations. Between 2014 and 2020, Alibaba has expanded their balance sheet by $92 billion in relation to equity investments (incl. goodwill recognised). In the same period, the ROAs have dropped from 26% to 13% and ROIC has fallen from 33% to 8%.

Alibaba management justifies these acquisitions saying that they are linked to the building of a digital ecosystem. However, most of the businesses don’t make any money (eating up most of the core business’ free cashflow) and claims around strengthening the ecosystem often seem tenuous. For example, in 2015, Alibaba invested $590 million into Meizu, a Chinese smartphone manufacturer, which besides having nothing to do with Alibaba’s core business also meant entry into a highly competitive space. A now struggling Meizu needed a financial bailout from the government in 20197. Alibaba Pictures Group, which began in 2014 as a 60% stake in ChinaVision Group, has been another sinkhole of capital for Alibaba shareholders. The company has accumulated $500 million in losses, after four years in the red8.

Some of these acquisitions are in fact so outlandish that Alibaba’s management team cannot claim synergistic benefits for the core business. Consider South China Morning Post, where Joseph Tsai was explicit about needing to control the narrative presented on China9. Or the $192 million purchase of 50% of Guangzhou Evergrande Football Club, which appears to be a vanity project10.

This raises the question: either Alibaba management team are wayward capital allocators going unchecked on account of poor oversight, or they have had no choice but to make such investments. To labour the point, they either had to make these investments to sustain the ecosystem, in a world of increasing competition from Tencent and venture capital funds (VCs) or such outlays are a necessary quid quo pro to sustain their licence to operate in the eyes of the government. Neither conclusion is comforting for minority investors.

Organisational Culture

In 2002, with the original business Alibaba.com on the road to success, Jack Ma handpicked a few employees to join a new project from his apartment in Hupan Garden, where Alibaba was conceived three years earlier. This team would go on to create Taobao and in the process develop an independent identity. In 2004, Alipay was created in the same way. Alibaba has called its culture the “Hupan culture”, which is basically an embodiment of a very entrepreneurial and demanding environment.

On the flip side, this working culture has gruelling aspects, especially in terms of working hours, which is referred to as the “996 work schedule” (9am to 9pm, 6 days a week). On a GitHub project titled “996.ICU”, Alibaba was listed as having among the worst working conditions amongst tech companies. Even the People’s Daily, China’s leading newspaper, has called out Alibaba on their “encouraged overtime” and argued that it violates China’s labour laws. Jack Ma has defended the working hours as a privilege11.

Another more troubling aspect of the cult-like working culture at Alibaba is the storied testosterone-driven environment that allows shouting matches in meetings. ‘Ali fellows’, as employees are called, have been described as radical , aggressive and reckless with ambition12.

Environmental and Social Stewardship

Despite being one of the largest companies in Asia, Alibaba’s environmental disclosure remains non-existent. To distract from the fact, there are some glossy reports showcasing the single data centre that operates on 100% renewable energy. Naturally, Alibaba, with its billion annual deliveries, is a big contributor to greenhouse gas emissions and packaging waste, and yet their efforts to use “green packaging” appear to be greenwash. For a company of this size, such poor disclosure and effort around sustainability is unacceptable.

In terms of social stewardship, Alibaba does help improve business efficiency which gives weight to its stated purpose to help SMEs and small merchants.

However, Alibaba’s ability to operate appears to be increasingly dependent on complying with stricter demands from the government, which have serious consequences for broader society. For example, in 2019 it was disclosed that the government propaganda app, “Xuexi Qiangguo” (“Study to make China strong”) was developed by Alibaba13. Similarly, through its data platform, Sesame Credit, Alibaba has played a crucial role developing China’s social credit scoring system, and its Alibaba Cloud business was recently found to be offering Uighur facial recognition services to its Chinese clients14.

How can minority shareholders defend the fact that they are helping fund the mass surveillance of an ethnic minority, much to the dismay of human rights advocates? Why does Alibaba deem it necessary to help the government in such a way? Do they even have a choice in the matter, and is it simply the necessary tax that Alibaba must pay to sustain the political patronage that gave rise to the company’s scale and dominance?

Quality of Franchise

Alibaba is a conglomerate whose core focus is e-commerce. It also owns a number of related and unrelated businesses. In a nutshell, the franchise consists of:

- E-Commerce platforms including Taobao (marketplace), TMall (third-party platform for brands), Ali-Express (platform to buy direct from manufacturers), Alibaba.com and 1688.com (B2B), Hema (brick and mortar grocery), Alimama (similar to Google AdWords), and Cainiao Network (logistics).

- Alibaba Cloud (similar to AWS and Azure)

- Youku (similar to YouTube) and other digital media assets including AutoNavi (similar to Google Maps)

- Ant Financial: dominant payments and online financial services business

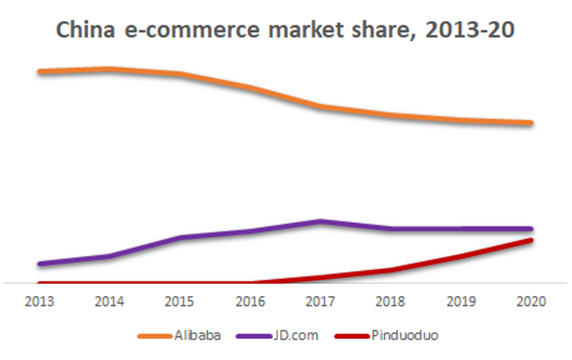

Alibaba has 60%+ share of the e-commerce market, with some 750 million active customers. The main e-commerce sites under Alibaba have over 10 million merchants and one billion items on sale.

Taobao, which translates to “searching for treasure”, is the leading online marketplace selling virtually everything (like Amazon) but without inventory risk (unlike Amazon). Just like “to Google” is eponymous with searching in the West, to “Tao” is to search for a product online in China, meaning Taobao has been an instrumental force behind China’s online consumption boom . Taobao is extremely profitable as it sells advertising space to merchants who want to be more visible. TMall meanwhile is a giant online shopping mall with more than 60% share of cross-border e-commerce. For global brands with aspirations in China, Alibaba is a complete solution given its access to content promotions, for example online influencers/celebrities, and logistics. As these foreign brands mature, they can move into a TMall flagship store, and even expand offline with Alibaba’s O2O efforts (Sun Art, Intime, Freshippo).

This import infrastructure and logistics dominance was built with Cainiao Network and a group of delivery companies collectively known as the Tongda Operators to create a huge competitive advantage. The fact that Alibaba has managed to develop such an ecosystem, in a seemingly capital light manner, has allowed them to take share and become more entrenched, whilst protecting their high returns on equity.

It is important at this stage to recognise that Alibaba has been able to build such a dominant e-commerce franchise thanks to the special treatment it has received from the government. In Alibaba’s early days, the Chinese government, led by the Shanghai faction, supported the company by using Taobao and Tmall to facilitate billions of dollars of transactions between various government agencies16. Meanwhile, global internet peers have either been discriminated against (eBay, Walmart) or have had to exit as a result of direct privacy violations demanded by the local authorities (Google, Twitter). The government links and opaque ownership structure that we detailed in the “Quality of Stewardship” section, alludes to the fact that Alibaba was “chosen” by the authorities. Its privileged position means its franchise sits on potentially shaky ground, because what happens when Alibaba stops being the poster child for China Inc.? Worse, what if the authorities actively decide to make life miserable for Alibaba, in the way they have for their competitors in the past?

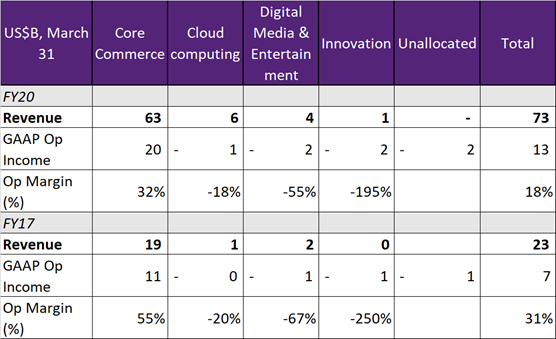

Furthermore, as we look at the evolution of margins and returns at Alibaba, two things become immediately clear.

Source: Company filings

Firstly, competitive pressure in the core e-commerce business has led to market share losses and a steady erosion of profit margins. Competitor JD.com has carved out an advantage by building its own logistics infrastructure, which allows it to guarantee quicker delivery services, and newer competitor Pinduoduo has taken aim at the lower-end of the market, i.e. lower-tier cities, through its focus on value and group-purchasing. Given the amount of capital flowing into the sector and the growing risk of anti-monopoly regulations, the market share loss does not appear temporary. Alibaba has also been less successful in their international efforts as Lazada’s initial promise has failed to materialise, and their US and European expansion plans have faced cultural and competitive challenges. Investments in lower margin businesses such as Freshippo (new retail) and Cainiao Network (logistics) have also diluted returns.

Source: Company filings

Secondly, Alibaba has been investing in its digital marketplace under the premise that greater engagement will drive loyalty and spending. However, none of these newer businesses make any money. As we discussed earlier, such investments are perhaps necessary to maintain the digital ecosystem that Alibaba promises to be, or more cynically these investments could be the necessary quid quo pro arrangement that Alibaba has with the government in order to sustain a privileged position. The competition with Tencent, Meituan, and others to build the most comprehensive ecosystem (or “super-app”) appears to be driving down overall returns. For example, in areas such as local services, where Alibaba, via Ele.me, has been pitted against Meituan, the competitive landscape has been extremely challenging. The cloud business, while likely profitable in the future, has also seen its global expansion plans dented by concerns over privacy.

Finally, Ant Financial is worthy of a separate mention. The Alipay digital payment platform began as Alibaba’s answer to PayPal, providing a simple escrow mechanism to improve trust between buyers and sellers. Its success contributed towards eBay’s downfall in China, where PayPal was not allowed to operate. In time Alipay has evolved to become the most popular online payment tool in China from which Ant Financial has been able to cross-sell higher margin financial service offerings, including wealth management, loans, and insurance in a market dominated by highly regulated SOE banks.

In 2018, Ant Financial launched an online platform called Jiebei (“just borrow”) which offers short-term unsecured loans to consumers. Ant Financial then approached the banks with a simple proposition: They would match the banks, who were willing to fund these short-term consumer loans, with Alipay users, whilst also providing the banks with credit risk metrics. Ant Financial, as the middleman, would channel back interest payments to lenders, whilst also collecting an origination fee. Crucially though, it was the banks, not Ant Financial, taking the financial risk. Ant Financial quickly became the largest originator of unsecured loans to individuals in China and now accounts for nearly 20% of the country’s outstanding short-term debt17. But this success has invited regulatory scrutiny as weaker financial institutions with poor risk-management capabilities have become very dependent on Ant Financial to source the loans, whilst at the same time bearing the default risks.

Alipay’s disclosures also reveal that Alibaba’s core e-commerce franchise is currently over-earning thanks to preferential long-term commercial agreements between Alibaba and Alipay. If Jack Ma, who controls Alipay, decided to start charging Alibaba a market rate for the payment processing fee, this would wipe out some $6 billion of profits and the ROE for Alibaba Holdings would fall from an attractive 24% to a more mediocre 16%.

The Chinese regulators have tightened their scrutiny on the Alibaba group. In November 2020, Ant’s IPO, which was set to be valued at $300 billion making it one of the most valuable financial services businesses in the world, was postponed because the financial regulator demanded that Ant Financial hold 30% equity against the loans being originated from partner banks. At the time of writing this note, the State Administration of Market Regulation (SAMR) has also launched anti-trust probes against Alibaba and is examining potential abuse of market power. It appears that the political winds have started to change direction, and Alibaba’s privileged position is increasingly challenged.

Quality of Financials

Throughout its history as a listed company Alibaba’s financial statements have invited scepticism. Ahead of the New York IPO, with various Alibaba entities under increased scrutiny, Alibaba Pictures admitted to accounting irregularities18, leading to broader questions about accounting credibility.

We have two primary concerns with the accounting at Alibaba:

The first concern is the aggressive manner in which Alibaba marks its assets, something that calls into question the true value of their balance sheet and asset growth. As a case in point, in the 2017 report, Alibaba disclosed that they were carrying an investment in Alibaba Pictures worth $4.4 billion, at a time when its market value was $2.1 billion. They defended their decision to not mark the asset down with a statement that read:

“We believe that the decline in the market price of Alibaba Pictures is primarily due to limited awareness among the investors of its long-term business prospects”.

In 2018, they finally took an impairment charge, but this was offset by a “write up” in Cainiao Network for the same amount.

Which brings us to the second concern that we have, the recognition of gains associated with the acquisition of related companies. Alibaba employs a “step up valuation” approach, which works very simply as follows: Firstly, Alibaba acquires 49% of a company at $100, meaning they book an asset entry of $49. Next, they buy a further 2% of the company for $6 determining the value of the company to be $300, meaning their original investment needs to be re-marked. However, with the subsequent investment Alibaba now owns 51% of the company, so is obliged to reclassify its original equity investment as a subsidiary company. This reclassification values the overall investment at $153. All considered, for spending $6, they recognise an accounting gain of $104.

This is not a hypothetical example. Going back to the Cainiao Network acquisition, Alibaba invested $803 million in the company in 2017 which took their ownership from 47% to 51%. Having consolidated Cainiao Network as a subsidiary, Alibaba was at liberty to take a positive revaluation gain of $3.6 billion on their original investment, which was made a few months earlier.

Not all such step-up acquisitions have detailed footnotes like the Cainiao Network example. Often hundreds of millions of dollars of write ups have no explanation at all.

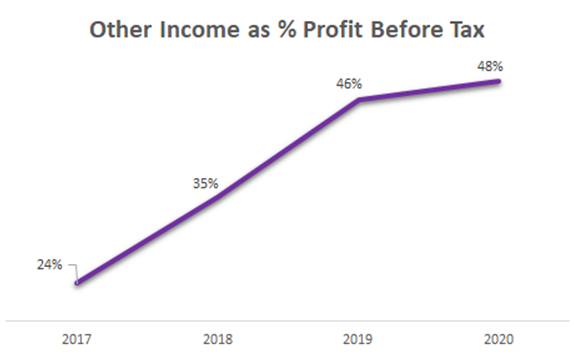

Is this revaluation of assets material? In short, yes. Almost half of Alibaba’s earnings are explained by such revaluation techniques, and the opaque methodology and convoluted ownership structure raises serious questions about the intentions of such aggressive accounting.

Source: Company filings

The obvious question that anyone should have at this stage is that if this is such a big deal, why are the regulators not acting? As per Alibaba’s latest annual report, in the US the company remains subject to an ongoing SEC investigation into potential violations of federal securities laws that commenced in 2016. In particular, the SEC has raised questions about their accounting practices for Cainiao Network, general policies for related party transactions and the operating data for the Singles Days shopping festival. It is not very reassuring that the Chinese authorities do not allow overseas auditors or authorities to audit local companies. The US Congress and SEC are considering options that force Chinese companies to become more transparent, to the extent that they are evaluating the threat of delisting companies that do not comply19.

Growth and Valuation

Since Alibaba does not make it onto our quality list, we would normally not attempt to assign a fair market value to the business. Given the opacity of the financial disclosures, the exercise is rather academic.

Most investors value Alibaba on its earnings potential and we feel compelled to point out (again) that a simple P/E ratio is fairly misleading since half the earnings are related to non-cash accounting gains and so earnings should be adjusted as such.

If we assume that our concerns regarding stewardship and financial quality are addressed, and that Alibaba is able to prosper despite the loss of government support, then the valuation exercise that we would follow might be summarised as follows:

Over the past decade, China’s e-commerce growth has been more than stellar. Consumers leapfrogged offline retail which largely explains why Chinese e-commerce penetration far exceeds countries at a similar stage of development in terms of GDP per capita. Chinese online retail GMV (Gross Merchandise Value) stands at $1.7 trillion, making it larger than the next ten countries combined and 2.5x bigger than the US market. Two statistics stand out for China: i) online retail already represents over a quarter of consumer goods sales20 (vs. 15% for the US market) and ii) roughly $1.2k or 13% of Chinese GDP per capita (c 9k) is spent online (vs. 4% for the US market).

We would assume that Chinese GDP grows at 5% for the next decade, and that by 2030 the consumption of goods is a third of GDP (vs. a quarter for the US today). At the same time, we would expect online penetration to reach 50%, which would equate to an 8% annual growth in GMV for China’s e-commerce market. We expect Alibaba will continue to lose market share on account of stronger competition and tougher anti-trust sentiment, however, for the sake of this valuation exercise, we give Alibaba the benefit of doubt and assume they maintain 50% market share. We also attribute a higher take-rate in 2030, on account of a positive mix shift from Taobao to TMall.

Such a scenario translates to revenue growth of 14% over the next decade for Alibaba’s domestic e-commerce business. Among the other businesses, the greatest prospect is Alibaba Cloud. Despite our concerns that there is rising competition in cloud from Tencent and Huawei, and that international growth might be limited, we are still ok assuming a generous 20% growth over the next decade, with margins improving from very negative to levels comparable to global peers such as Azure and AWS. For Alipay, we assume that media reports are true, and that tougher regulation will mean the business model reverts back to focusing on payments.

Our long-term predictions suggest Alibaba can generate $60 billion of free cashflow in 2030. Working on the assumption that Alibaba will be a much more mature business in 2030, we would expect our investment to at least generate a 5% free cash flow yield. This implies Alibaba should be worth $1.2 trillion in 2030, and if we then factor in appropriate adjustments to the share count for share-based compensation then we would expect to earn a 3% return in dollars from today’s share price .

All of this assumes that Alibaba management will not conduct value-destructive M&A, that cashflows will eventually be distributed to minority shareholders, and that there will be no further leakage from Alipay or other related parties. As discussed, we have also assumed that despite a tougher regulatory environment, Alibaba can maintain its leadership position. When we consider all of the potential risk the investment case is very unfavourable from a risk-reward perspective.

Conclusion

Alibaba has built a dominant franchise with high returns on capital and delivered very strong earnings growth since inception. This has invited a lot of investor interest and resulted in strong share price performance for several years. However, Alibaba fails our stewardship test, which changes our perspective of the company’s franchise and growth prospects.

Its competitive position has been underpinned by connections and support from the government. If the political winds change, as they appear to be at the time of writing this note, Alibaba’s privileged position may come under threat creating headwinds for the business.

We see the high returns on capital in a more sceptical light because of the opaque accounting; a situation made worse by non-existent oversight at board level, a complex ownership structure, and a culture known to be aggressive. It is also difficult to give Alibaba management the benefit of doubt for their M&A strategy which has diluted returns and enriched those at the top of Alibaba and their friends.

Coming back to the question of purpose; Alibaba’s purpose has drifted from its original intent of helping small Chinese businesses. It now appears to be serving the interests of the government and its original shareholders.

History is littered with examples of great businesses with poor stewardship, where poor stewardship eventually undermines the business. We appreciate that our view on Alibaba is unpopular and we have often been called out for missing out on an “obvious investment”. At Aikya we are focused on protecting downside and sleep better at night knowing that we have not exposed our clients to the risk of permanent capital loss.

1Alibaba’s Link to Elite Military Family Is Etched in Stone – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

2When Enron Met Alibaba: The Rise of VIEs in China (hbs.edu)

3Alibaba tweaks a controversial legal structure | The Economist

4Alibaba: A Case Study of Synthetic Control (harvard.edu)

5 Alibaba Founder Jack Ma’s Recent Deals Raise Flags – WSJ

6Busy At Home: Alibaba Pictures’ $103M Loan To Jack Ma-Linked Studio (forbes.com)

7Alibaba-Backed Former Smartphone Highflyer Gets Government Lifeline (caixinglobal.com)

8Another Year, Another Loss For Alibaba Pictures As Pandemic Strikes (forbes.com)

9Alibaba buys South China Morning Post (cnn.com)

10Alibaba buys Chinese soccer club (cnn.com)

11Alibaba founder defends overtime work culture as ‘huge blessing’ | Reuters

12Method in the madness of the Alibaba cult | Financial Times

13Alibaba is the force behind hit Chinese Communist Party app | Reuters

14Alibaba offered clients facial recognition to identify Uighur people, report reveals | Alibaba | The Guardian

15“Alibaba: The House That Jack Ma Built”, Duncan Clark

16Chinese Government Has A Huge “Stake” In Alibaba (forbes.com)

17 Jack Ma’s Ant Group Ramped Up Loans, Exposing Achilles’ Heel of China’s Banking System – WSJ

18Alibaba Pictures Finds Possible Accounting Irregularities, Delays Results – WSJ

19SEC Pursues Plan Requiring Chinese Firms to Use Auditors Overseen by U.S. – WSJ

20National Economy was Generally Stable in 2019 with Main Projected Targets for Development Achieved (stats.gov.cn)

21As at 31st December 2020